Adventures in Museum Research

©2005

I’ve done my share of research and I’ve built a career on writing and creating exhibitions about American female inventors. My wife and I have collected artifacts relating to female inventors for decades. However, it wasn’t until I left wife and home in the Midwest to study female patentees from 17th and 18th-century Britain that I understood all the joys of researching in a museum.

My quest for information about these British inventors led me east to visit the Hagley Museum and Library, in Wilmington, Del., to review their copy of Bennet Woodcroft’s compilation of British patents from 1617 to 1852. My goal was to review the 4,190 patents issued between 1617 and 1816 and to identify as many female patentees as I could.

For a week I worked through page after dusty page of decaying paper, photocopying the occasional patent that had a woman’s name and brushing yellowed paper shards from my clothes. At the end of a long Friday afternoon, I found patent number 2485, granted in 1801 to a woman named Ann Young. It was for a musical game, described as a:

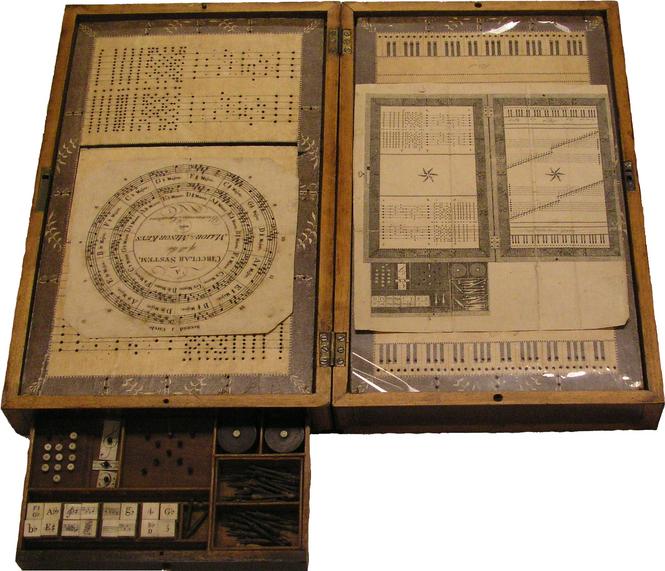

. . . new invented apparatus consisting of an oblong box, which, when opened, presents two faces or tables, and of dice-pins, counters, &c. contained within the same, by means of which six different games may be played, which besides being amusing and interesting . . . are at the same time an improving exercise . . . [in] the fundamental principles of the science of music, particularly all the keys or modulations, major and minor, . . . signatures, musical intervals, and chords, discords with their resolutions . . . .

The Hagley librarians waited patiently while I photocopied the hefty 23-page document, the thickest patent I had found so far. Exhausted, I returned to my hotel to plan my weekend as a tourist in Wilmington.

The hotel desk clerk recommended a day-long visit to Winterthur, the “American country estate” built by Henry Francis du Pont and his father in the early 20th century. I took the holiday tour (clearly the tour-de-jour in December), a cold tram tour of the grounds, and, as the staff member who greeted me suggested, the Private Spaces & Gaming Places tour—an exploration of “spaces, including bedrooms, that reveal how early Americans and the du Ponts spent their personal and leisure time.” This last tour turned out to be the highlight of my visit.

In one of the rooms, I noticed a game on a round table. There was no doubt; it was the game described in Ann Young’s 1801 patent. I didn’t shout. I didn’t disturb the other tourists. However, I could not focus on the guide for several more rooms. Here was an artifact that I coveted.

Afterwards, I told the friendly person who had recommended the tour that I wanted to learn more about this artifact. She asked several tour guides about the object and one recognized the musical game. It was in the Imlay Room, she said, and she remembered reading about the object in Guide Lines, the in-house Winterthur newsletter. Armed now with more information, she gave me the phone number of a registrar at Winterthur. She wished me good luck in my quest, and reminded me that I could not call until Monday.

Monday came and I called with some trepidation. My own experience as a collector and as a curator of exhibitions taught me that museum people are a) busy and b) very protective of their toys. But the registrar was friendlier than I expected. She checked her records and verified that Winterthur owns the artifact I sought. Yes, she told me, there is a file. Yes, I can see the file. No, I cannot drive right over because today is Monday and the museum is closed to the public on Monday. No, I can’t come to her office on Monday even though she is there. I can come on Tuesday, but I would have to see one of her colleagues, Grace Eleazer, because she would be out for the day. No, she hasn’t seen what is in the file, but I could do so on Tuesday.

Tuesday came too slowly. Once Ms. Eleazar welcomed me into the registrar’s office, she retrieved the file and left me alone to study it. The file was thin—just a few descriptive remarks including size and accession information. Only one paragraph! I also found some difficult-to-read, handwritten notes about conservation efforts. That was all.

I wondered if the conservator’s notes might provide additional clues. I asked about conservation photos. The very patient Ms. Eleazar walked me to the photo services department where Susan Newton, the person in charge, quickly found negatives of before and after pictures. She arrayed them on a huge light table and left me alone with the images. They were great! I dreamed of publishing one or more in a clever article about British women inventors. I arranged for a few prints to be sent back home to the University of Minnesota.

When I returned to the registrar’s office, I inquired about the Guide Lines article the tour guide had mentioned during my first visit. After some digging, Ms. Eleazar returned with two copies, one for me and one for the file. The article was detailed and scholarly, written in 1995 in the dry style of an intern who has not yet earned the right to go beyond the many footnotes.

Before I left, Grace (we were now fast friends and on a first-name basis) introduced me to one of her colleagues, Lynn Swain, who was especially interested in my work. Lynn had recently found papers in her attic describing her great-grandmother’s employment in the patent office. That piqued my interest. I knew from curating the U.S. Patent System’s bicentennial exhibition, “A Woman’s Place is in the Patent Office,” that the Patent and Trademark Office was the first U.S. government department to offer women equal pay for equal work. I mentioned that Clara Barton was one of those early employees—this bit of trivia cemented our friendship—and she promised to send me her great-grandmother’s notes. I promised to visit again when I was in Delaware. I went home with new friends, excellent documentation about the 1801 musical game patent, and this story to tell.

My trip east yielded more than a typical week’s worth of research on an obscure 19th-century invention. It also reminded me about the research adventures lurking behind a museum’s doors.

Oh, yes. In the 200 years beginning with 1617, 4,190 British patents were granted. Of those 40, include the name of a woman. Of the 40, seven were granted to women (often widows) for the invention by dead husbands or debtors. Thirty-three of the patents were granted to female inventors, but Sarah Guppy had two patents during this period, so, consequently 32 “inventresses” are on the list. One of them is Ann Young whose musical game is in the Imlay room at Winterthur Museum.

—Fred M. B. Amram. The author is a retired award-winning professor of communication and creativity. An inventor himself, Amram has published books and articles about creativity and curated exhibitions about inventors.

Photo by Sandra A. Brick